Baker v. Carr

Baker v. Carr is one of the most significant Supreme Court cases on redistricting, leading to a new era of legal challenges to legislative maps.

The Case in Brief

History. For nearly 200 years following the nation’s founding, there were virtually no federal guidelines or requirements for redistricting, creating wildly disproportionate maps in many states. Despite many voters’ concerns, the Supreme Court considered the redistricting process nonjusticiable and refused to get involved.

Case Facts. Charles Baker and other Tennessee voters sued the state for failing to redistrict to reflect growth in its suburban and urban populations. They argued the existing maps overrepresented rural voters and thus denied equal protection of the law, required by the 14th Amendment.

Majority Opinion. The Court found that federal courts could address the constitutionality of redistricting. It did not rule on the Tennessee voters’ complaints, ordering a lower court to rehear the case with the new guidance.

Results. The decision inspired a decade of lawsuits challenging legislative maps, resulting in the Supreme Court establishing new standards for redistricting. It also laid the foundation for the “one person, one vote” principle, requiring districts to have roughly equal populations. Almost every state had to redraw their maps to conform to these changes, leading to a complete makeover of the political landscape.

History

In Colegrove v. Green (1946), three Illinois voters sued the state, arguing that its congressional districts “lacked compactness of territory and approximate equality of population,” violating the Constitution and federal law. The Supreme Court found that Congress and the states had sole control over redistricting. As a result, the Court ruled it could not resolve the legislatures’ failure to carry out that duty due to the political question doctrine. Colegrove established the precedent that the Supreme Court could not rule on redistricting challenges, as it is a nonjusticiable issue.

Case Facts

Like many states across the country, Tennessee lost a significant portion of its rural population following World War II as many Americans moved to suburban and urban areas. However, the state legislature had not redistricted since 1901, resulting in districts with wildly different populations.

In 1959, a group of Tennessee voters — including Charles Baker — sued Tennessee Secretary of State Joseph Carr, claiming that the state legislature’s failure to redistrict violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. This Clause says that a state cannot “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” These voters argued that the districts’ substantial population differences made some people’s votes matter more than others, inherently denying equal protection.

State officials argued that federal courts did not have the power to provide a solution in this case. They claimed that the state’s political process must function without judicial interference. Additionally, they argued that, even if the courts could hear the suit, the Constitution does not require state legislative districts to have equal populations.

A federal district court rejected the voters’ challenge, saying it did not have the authority to rule on the issue, consistent with the Colgrove ruling. Baker and his fellow citizens appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which heard arguments in 1961.

Majority Opinion

Redistricting is a justiciable issue under the Equal Protection Clause. Federal courts have the authority to enforce the equal protection requirement against state officials and legislatures.

Nothing prohibits federal courts from determining if states have irrationally drawn their districts.

This challenge does not present a “political question” that courts cannot rule on.

The District Court must rehear Baker’s challenge to the state’s legislative districts on the merits.

Dissenting Opinion

Court precedent says that federal courts have no role in deciding these cases, as it has consistently refused to hear challenges to states’ redistricting processes.

The Constitution leaves redistricting to the states, and there is no constitutional requirement for how they must carry out that task.

The majority’s ruling threatens our federal system, disregarding state legislatures’ independent judgment. It unconstitutionally broadens our judiciary’s power at the other government branches’ expense.

The Supreme Court must remain impartial to maintain the confidence of American citizens and thus cannot rule on political issues. This includes redistricting, where federal courts cannot be involved in the debate.

Related Cases & Events

Rucho v. Common Cause (2019)

Vox

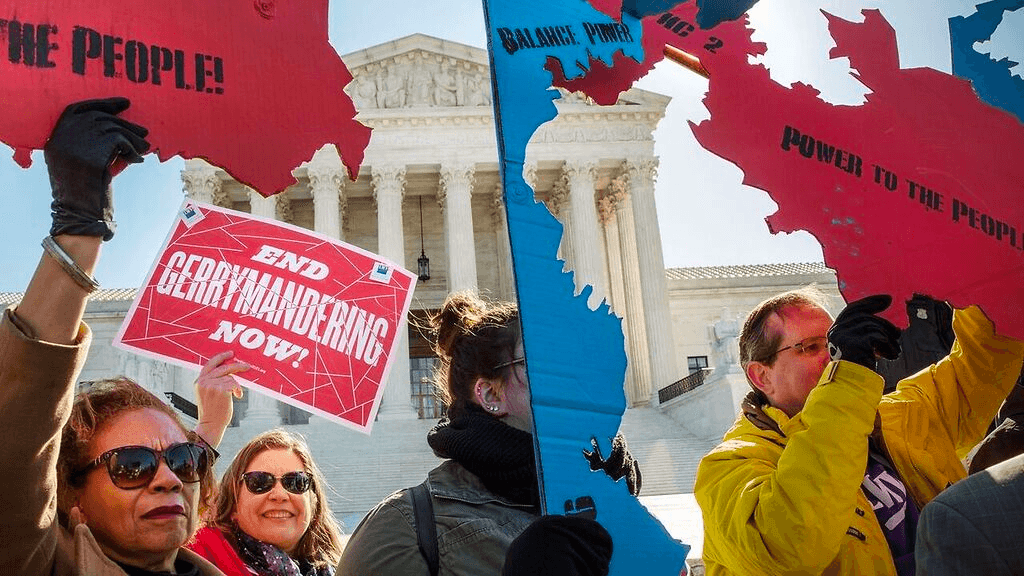

In 2016, two political organizations filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging that North Carolina’s congressional districts constituted an illegal partisan gerrymander. The District Court struck down the state’s map, ruling that state lawmakers had drawn it with clear partisan intent. North Carolina Republicans appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, arguing that the District Court had overreached its authority. In 2019, the Court issued a joint ruling in this and another gerrymandering case (Lamone v. Benisek). In its landmark 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court said that partisan gerrymandering claims present a nonjusticiable political question. Federal courts can still consider challenges to states’ maps if legislators drew districts based on race.

Discussion Questions

- What parallels do you see between Rucho and Baker v. Carr?

- Why do you think the Court found it can consider challenges to racial gerrymandering but not partisan gerrymandering?

- Explain your stance on partisan gerrymandering.

New Redistricting Cases

Associated Press

The 2020 redistricting cycle has seen extensive litigation as lawmakers, political parties, and interest groups have challenged new maps across the country. In North Carolina and Pennsylvania, Democratic majorities on their State Supreme Courts threw out new district lines from the Republican-controlled legislatures. As a result, Republican lawmakers in those states are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to consider whether state courts have the authority to interfere in this process. These legislators advocate for the “independent state legislature” doctrine that suggests that each state’s legislature can decide how to conduct federal elections without input from the other branches. Republicans claim state courts have taken authority the U.S. Constitution gives the legislatures. Meanwhile, Democrats argue that giving more power to state lawmakers could allow them to curtail voting rights.

Discussion Questions

- How do Republican lawmakers’ arguments in these cases compare to those of Tennessee officials in Baker v. Carr?

- Do state courts have too much power over the election process? Why or why not?

- What are the implications of the “independent state legislature” doctrine?

Redistricting Commissions

KQED

(KQED)

Amid concerns about gerrymandering, some activists have called for states to establish redistricting commissions. Many states already use some form of commission to help draw their legislative district lines, and various lawmakers at the federal level have even proposed requiring states to establish them.

In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that these commissions are constitutional (Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission). However, many critics — typically Republicans — argue that they take the authority that belongs to state legislatures. Additionally, they question how impartial these commissions can be and say they are less accountable to voters. On the other hand, supporters argue that letting lawmakers draw their own districts undermines the process’ integrity.

Discussion Questions

- Do redistricting commissions undermine state legislatures’ constitutional authority over elections? Explain your position.

- Are these commissions an effective strategy to combat partisan gerrymandering? Why or why not?

- What qualities should commissions prioritize when drawing new district lines? Competitiveness? Compactness? Something else? Why?

2020 Reapportionment

U.S. Census Bureau

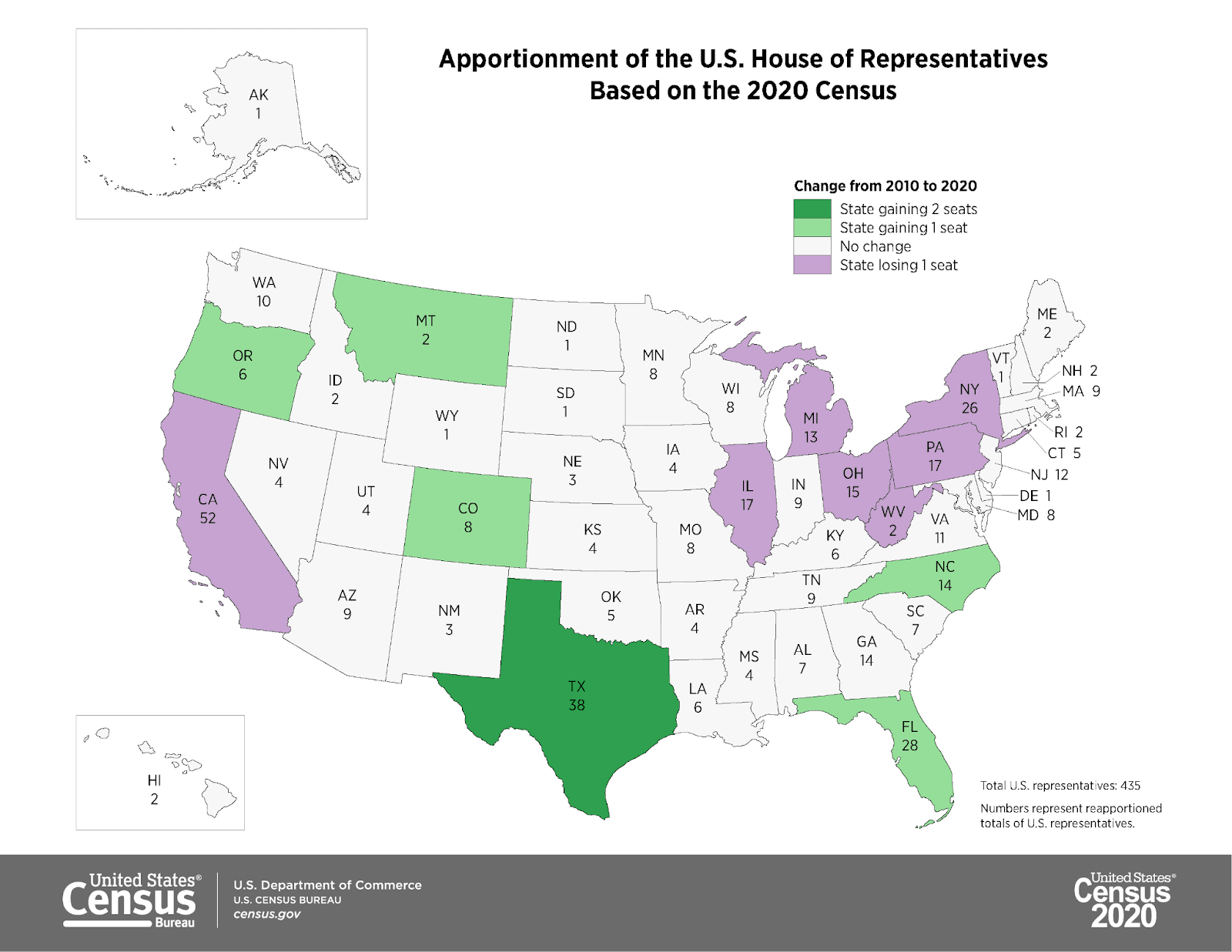

Following the 2020 reapportionment:

- Seven states lost one seat (California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York).

- Five states gained one seat (Oregon, Montana, Colorado, North Carolina, and Florida).

- Texas was the only state to gain two seats.

This reapportionment changes some election dynamics, as the process also corresponds with how many votes each state gets in the Electoral College. While each redistricting cycle presents an opportunity for manipulation, states that gain or lose representatives are especially susceptible to gerrymandering.

Discussion Questions

- Do you notice any trends in the population changes? If so, what are they?

- Have any courts had to get involved in the redistricting process, consistent with the decision in Baker v. Carr?

FRQ Practice

The Texas Constitution requires the legislature to reapportion its senate districts after the census. Following the 2010 census, state lawmakers approved a redistricting plan, and the Governor signed it into law. However, a federal court ruled that the new map might violate the Voting Rights Act, issuing an interim plan for the 2012 primaries that the legislature approved. Two registered Texas voters — Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenniger — sued the state, claiming the new map violated the Equal Protection Clause. While the districts were relatively equal according to the total population, they were substantially different when considering the total registered voter population. Evenwel and Pfenniger argued that the plan did not adhere to the “one person, one vote” rule.

The District Court dismissed their complaint, saying they failed to show the new districts violated the Equal Protection Clause. They ruled that Supreme Court precedent allowed states to use the total population for reapportionment. The voters appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously in favor of the state. The Court found that the “one person, one vote” rule allows states to redistrict based on total population.

Based on the information given, respond to Parts A, B, and C.

- Identify the constitutional clause common to Baker v. Carr (1962) and Evenwel v. Abbott (2016).

- Based on the constitutional clause identified in Part A, explain why the facts of Evenwel v. Abbott led to a different holding than the holding in Baker v. Carr.

- Describe a political action that members of the public who disagree with the holding in Evenwel v. Abbott could take to attempt to impact the redistricting process.

Important Terms

Census. Every 10 years, the federal government attempts to count every person residing in the United States by conducting a constitutionally-required census. The government uses this data for several significant purposes, including reapportionment.

Reapportionment. Following the census, the U.S. Census Bureau redistributes the 435 seats in the House of Representatives among the 50 states. The number fluctuates up or down based on population changes, but each state must have at least one representative.

Redistricting. After every reapportionment, any state with two or more representatives begins redistricting, where they redraw district boundaries for Congress and state legislatures. States often entrust this responsibility to their legislature, a commission, or some combination of the two.

Gerrymandering. Gerrymandering is when a redistricting body redraws lines to give a group an unfair advantage. They may do so by drawing the boundaries to benefit the incumbent political party (partisan gerrymandering) or dilute minorities’ voting power (racial gerrymandering).

Nonjusticiable. A case is nonjusticiable when courts are incapable or do not have the authority to rule on the issue.

Political Question Doctrine. The political question doctrine sets a limit on judicial power. If the Constitution reserves an issue to the executive or legislative branches, the courts do not have jurisdiction and cannot rule on it. Over time, the Supreme Court has changed its interpretation of which topics constitute a “political question.”