History

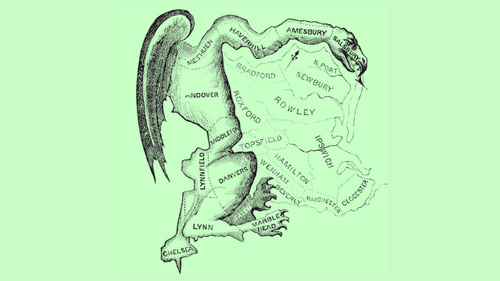

- 1812|

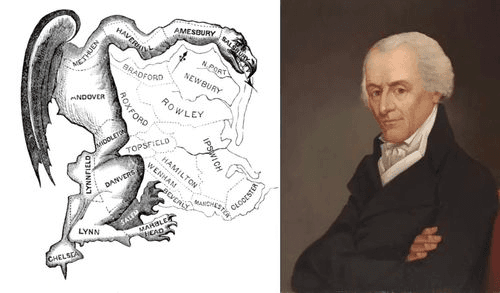

Elbridge Gerry

The term “gerrymandering” emerged in 1812 after Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a redistricting plan heavily favoring his party.

- 1962|

Baker v. Carr

Baker v. Carr is one of the most significant Supreme Court cases on redistricting, leading to a new era of legal challenges to legislative maps.

- 1965|

Voting Rights Act of 1965

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. This legislation sought to protect millions of minority Americans from discrimination.

- 2004|

Vieth v. Jubelirer

In recent years, beginning with Vieth v. Jubelirer, the Supreme Court has ruled that it cannot address partisan gerrymandering.

Introduction

Every decade, the United States conducts a constitutionally required census, which attempts to count every resident in the country. The census is incredibly consequential, as the U.S. Census Bureau uses it in a process known as reapportionment to determine how many representatives each of the 50 states will have in the House of Representatives. After every reapportionment, any state with two or more representatives begins redistricting, where they redraw district lines to encompass roughly equal populations. States usually entrust this responsibility to their legislature, independent commissions, or some combination of the two.

Census

Today, the redistricting process has become one of the most contentious political issues in the United States. When a state redraws its lines to advantage or disadvantage a specific group, it is called gerrymandering. While congressional gerrymandering has been around almost as long as Congress itself, the prevalence of demographic information and advanced statistical analysis programs has made it increasingly common and effective. Gerrymandering is also an issue between the balance of powers. When courts decide not to strike down gerrymandered maps, legislators become more brazen in their attempts to do so. These gerrymanders have long-lasting implications, changing election dynamics for the next decade.

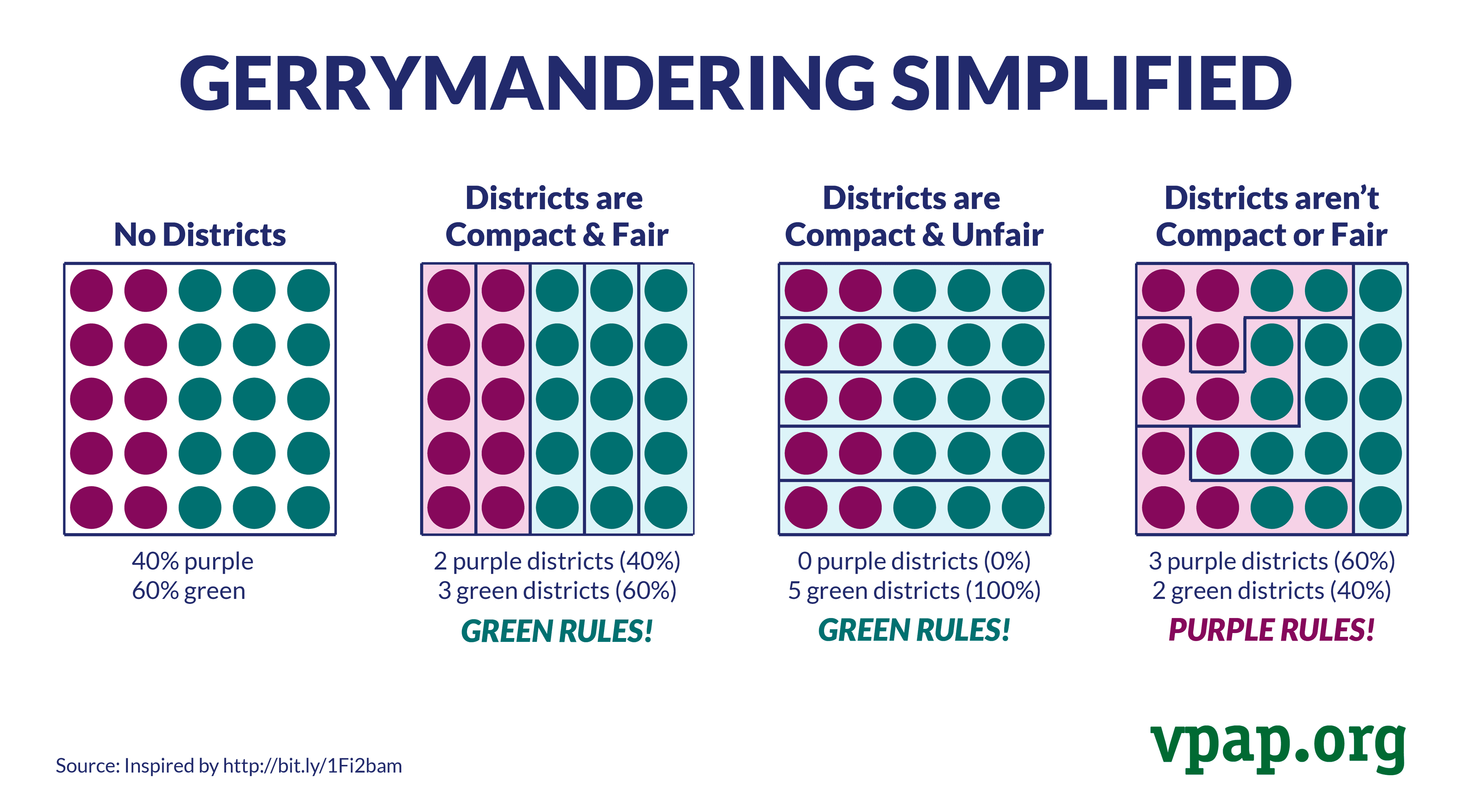

What is Gerrymandering?

Gerrymandering is the manipulation and redrawing of legislative districts to favor one’s party and/or hurt the opposition. It primarily comes in two forms: packing and cracking. Packing is when the redistricting party puts opposition voters into a small number of districts, giving them overwhelming victories in these districts but minimizing their impact on surrounding ones. Packed districts are often elongated, irregular shapes that group politically similar areas that are otherwise nowhere near each other geographically. Cracking is when a large group of compact, like-minded voters is split amongst several districts to dilute their voting power. Legislators employ both strategies to strengthen their party’s standing, protect incumbents, or both. Sophisticated computer software has allowed legislators to use these tactics with growing efficiency, and the issue has grown in importance as states undergo their current round of redistricting.

2020 Redistricting Cycle

The 2020 cycle gives a great example of gerrymandering debates following a census!

Following the 2020 U.S. Census came a procedure known as reapportionment, in which states can gain or lose congressional seats to reflect the population changes of the last decade. In all…

- Seven states lost a seat (California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York).

- Five states gained a seat (Oregon, Montana, Colorado, North Carolina, and Florida).

- Texas was the only state to gain two seats.

This reapportionment changed some election dynamics, namely that political power shifted away from the industrial Midwest and Northeast to the growing South. Some states only have one congressional seat, making their congressional election a statewide race (Alaska, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Delaware, and Vermont). However, most states have multiple congressional seats, so they must enter the controversial redistricting process after every census. These new maps have significant political implications, especially when one party controls the institution in charge of redistricting. So far, both parties have used their positions to increase their share of “safe” seats. There were several notable examples of gerrymandering in the 2020 redistricting cycle:

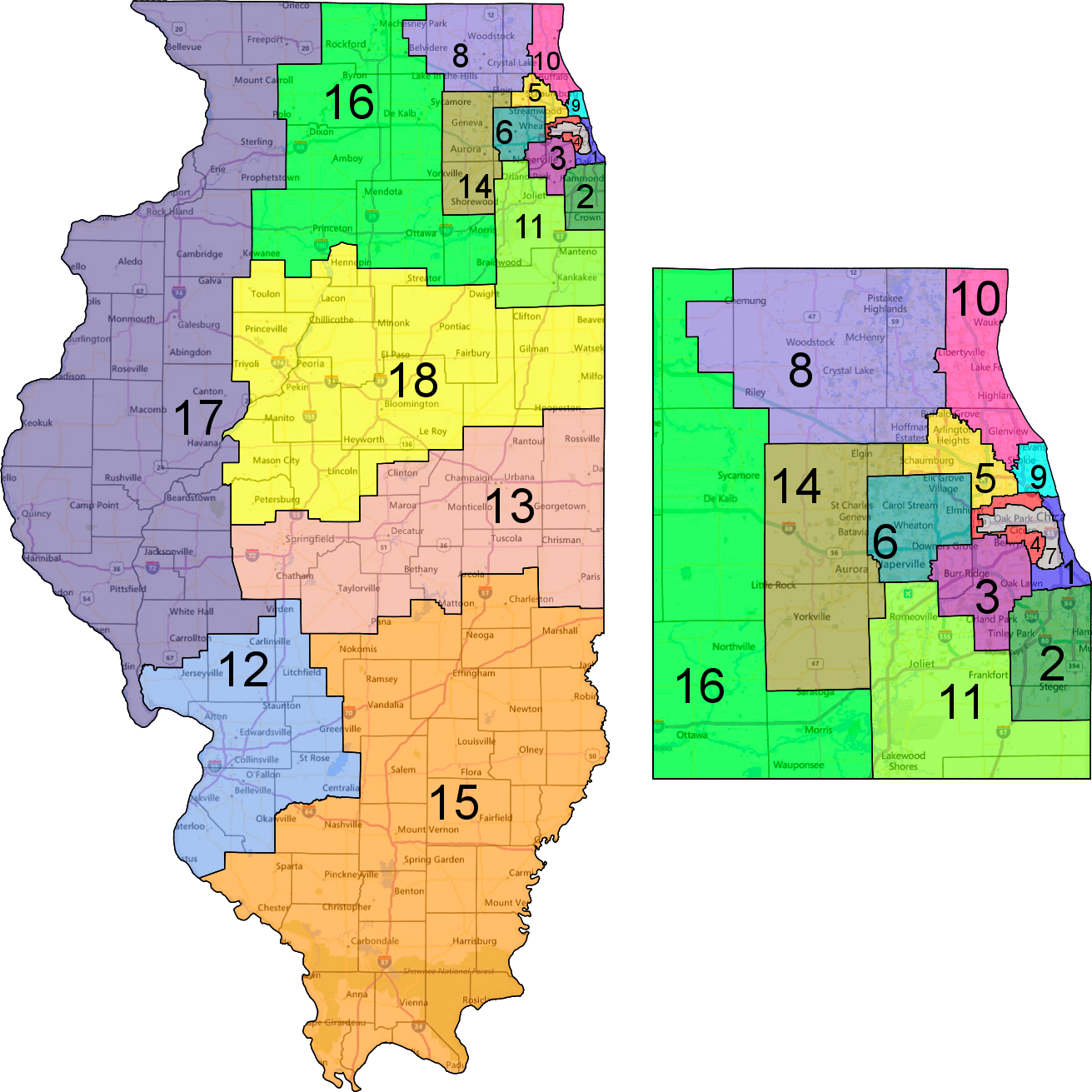

Illinois

Illinois was a rare example of a state where Democrats controlled the entire redistricting process. The Democratic-controlled state legislature proposed a map that Democratic Governor J.B. Pritzker approved. The state lost one of its congressional seats in the 2020 reapportionment cycle, so at least one of its members in the House would lose their job. Several Republican incumbents were put into the same districts, prompting some to announce their retirement from Congress after the 2020 term. Others had seen their relatively safe seats shift to likely unwinnable districts for a Republican. The approved map boosted Illinois Democrats. Compared to the old map, Illinois added two Democratic-leaning seats, eliminated two competitive seats, and lost a heavily Republican seat. All told, analysts expected Democrats to control at least 14 of the state’s 17 congressional seats.

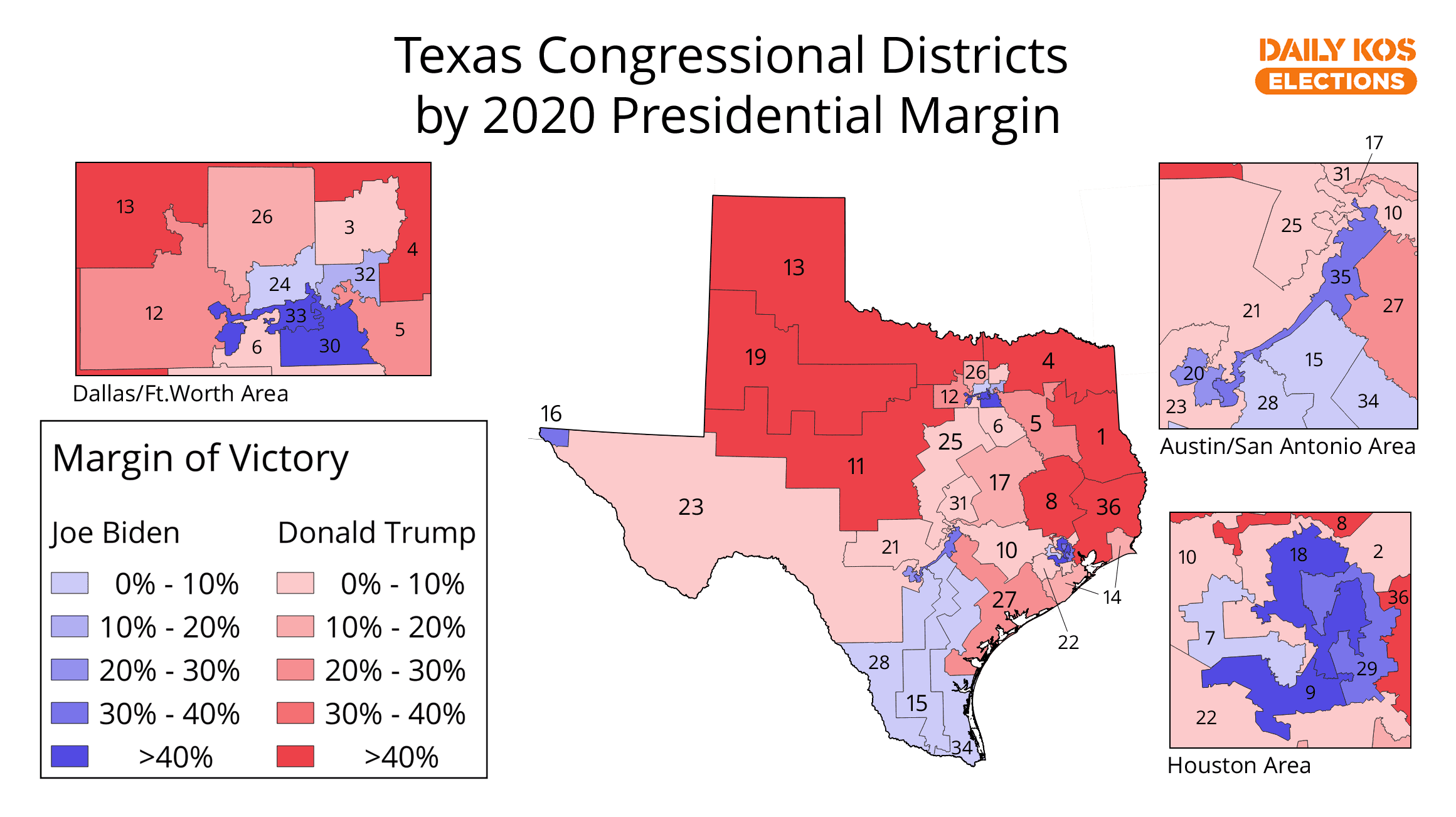

Texas

Republicans controlled the redistricting process in Texas, where Republican Governor Greg Abbott approved the Republican-controlled legislature’s proposed maps in October 2021. Texas saw the most rapid growth of any state over the last decade and gained two congressional districts in the 2020 reapportionment. Republican lawmakers in the state used this redistricting cycle to entrench Republican incumbents and reduce the number of competitive districts. Unlike many other states with Republican gerrymanders, Democrats gained three strong districts. However, this is significantly overshadowed by the increase of 10 Republican-leaning seats, leading to an overall loss of 11 competitive seats. Overall, trends projected Republicans to carry at least 24 of Texas’ 38 congressional seats. The Texas congressional map was contested by the Democrat controlled Department of Justice who joined several plaintiffs in challenging the redistricting plan as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. This effort failed and in a stunning rebuke of the racial charges, a Republican flipped a solid Democrat district in a heavily Hispanic district during a special election later that year.

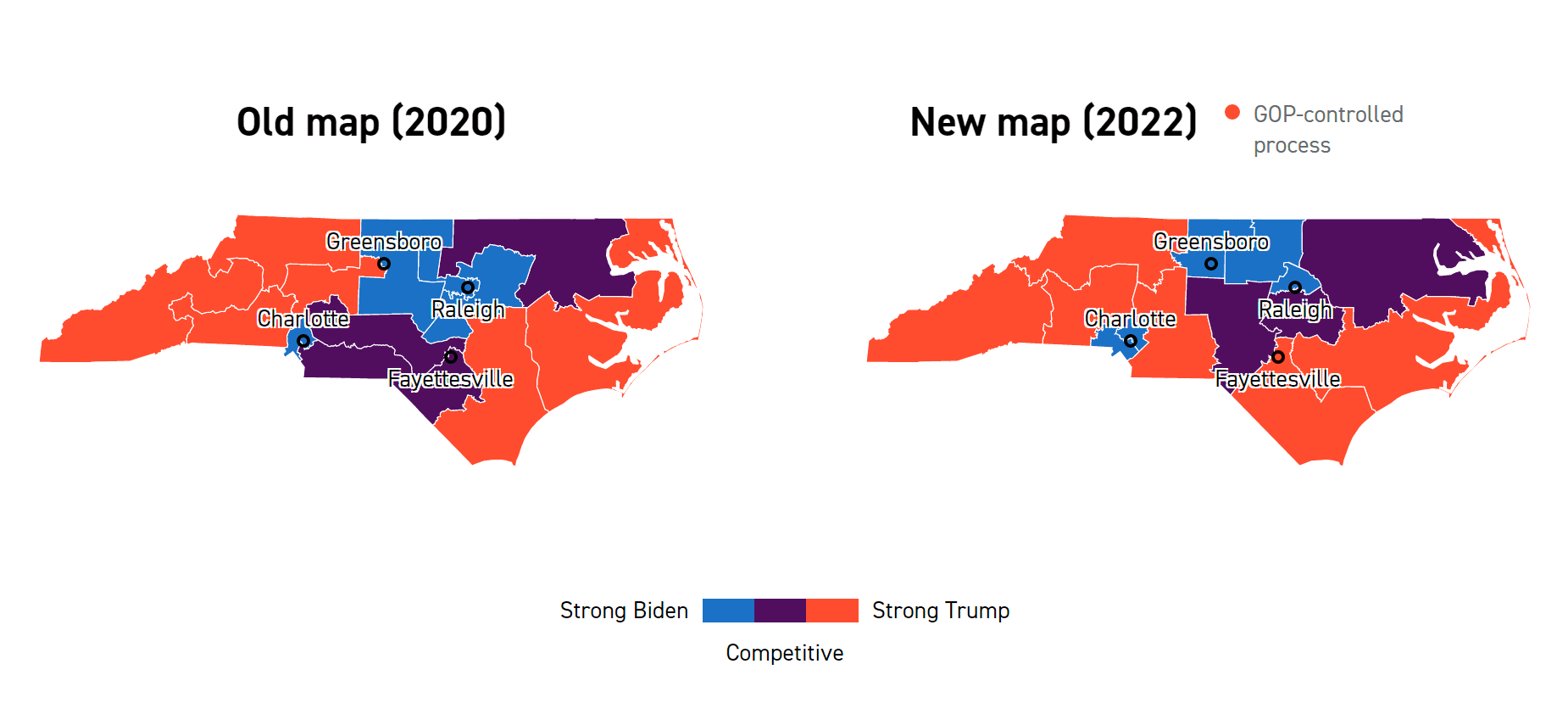

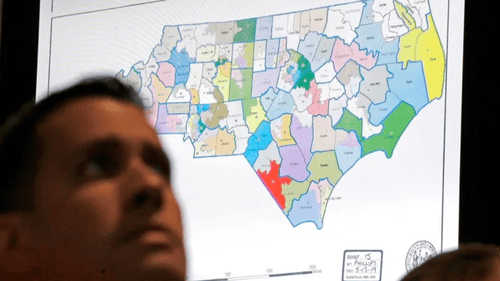

North Carolina

North Carolina distinguishes itself from almost every other state in its redistricting process, as its congressional maps originates from the state legislature but are not subject to a gubernatorial veto. This is especially relevant in the 2020 cycle, as Democratic Governor Roy Cooper had no say in the Republican-controlled state legislature’s approval of the new maps. North Carolina gained one congressional seat in the latest round of reapportionment, and Republican state lawmakers used this to enact an aggressive redistricting plan. According to pundits, Republicans were likely win at least 10 of the state’s 14 congressional districts under the legislature’s initially proposed maps. However, in a split 4-3 decision in February 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court invalidated the legislature’s maps for Congress and the General Assembly, ruling that they would give an unfair, long-term advantage to Republicans. They ordered the GOP-led legislature to redraw them. The new maps, which remained in place for the 2022 mid-term elections, showed a much more even split. Of North Carolina’s 14 congressional districts, political analysts said six favor Democrats and seven favored Republicans. Republicans asked the Supreme Court to halt the state court’s ruling and reinstate their old maps, arguing that the N.C. Supreme Court had undermined the legislature’s constitutional authority to redistrict. While the Supreme Court denied that emergency appeal, some conservative justices expressed willingness to consider that argument in the future.

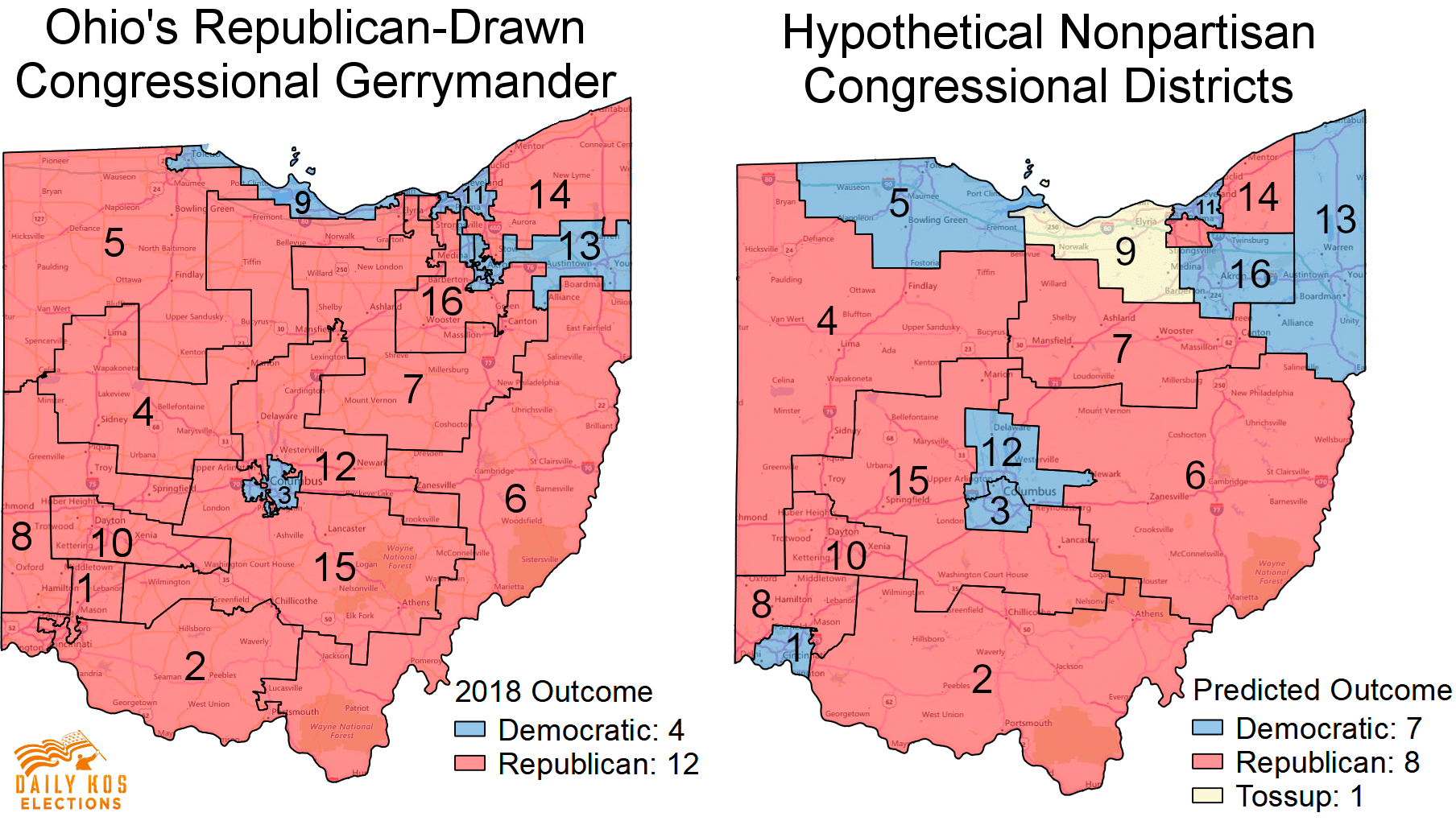

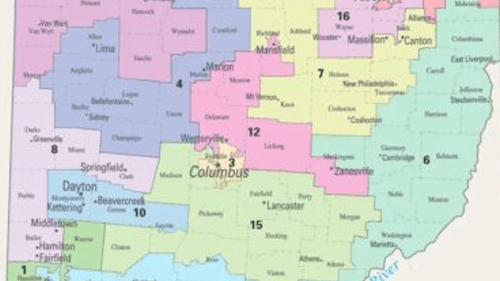

Ohio

In November 2021, Mike DeWine, the Republican Governor of Ohio, approved new congressional maps from the Republican-controlled state legislature. Ohio lost a congressional seat in the most recent round of reapportionment, granting Republican lawmakers a chance to tilt the maps in their party’s favor. These maps - passed along party lines - were widely considered to advantage Republicans. Under a 2018 amendment to the state’s constitution, creating a 10-year congressional map requires bipartisan support, but without it, the map would only last four years. However, in January 2022, the Ohio Supreme Court struck down the existing congressional maps. Political observers estimated the maps created at least a 12-3 advantage for Republicans in the state’s 15 congressional districts. Ohio voters are split roughly 54% Republican to 46% Democratic, prompting the Court to call the maps “infused with partisan bias” in their ruling. After the decision, the state’s lawmakers were on a 30-day deadline to propose new maps, but the 2018 reforms allow the Ohio Redistricting Commission to take over if they failed. In a similar January 2022 ruling, the state’s Supreme Court also struck down the new maps for the state legislature due to partisan bias.

Gerrymandering is not limited to congressional districts: if it is happening for the federal level, it is almost certainly also happening for state-level districts (see North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, etc.). For further resources and in-depth analysis of the 2020 redistricting cycle, visit the following websites: FiveThirtyEight’s What Redistricting Looks Like in Every State, Politico’s Redistricting Tracker, All About Redistricting, and the Princeton Gerrymandering Project.

Discussion Questions

- Do political parties only complain about gerrymandering when it hurts them?

- Could an independent redistricting committee help prevent district gerrymandering?

- If gerrymandering has been around since 1812, how can it be stopped?

Narratives

Left Narrative

Gerrymandering sabotages America’s elections by disproportionately advantaging political parties over the explicit will of the voters. Its continued use threatens the bedrock of American democracy. It is a domestic plot to undermine one of America’s most sacred values: free and fair elections. In practice, gerrymandering is the deliberate disenfranchisement of voters and is unacceptable. An impartial electoral process with an active constituency and healthy competition is vital to the strength of American democracy. Voters must choose their elected officials, not the other way around. Non-partisan, independent redistricting committees are the only way to ensure that.

Right Narrative

Political parties will only complain about gerrymandering when it does not benefit them. Legislators can use gerrymandering as a tool to protect themselves, but they can also use it to give a voice to minority communities. If you live in a district that heavily favors one side over the other, it may be more equitable for you if the redistricting party puts you in another one.

Bipartisan Narrative

Classroom Content

Browse videos, podcasts, news and articles from around the web about this topic. All content is tagged by bias so you can find out how people are reacting across party lines.

ACLU sues Ohio GOP lawmakers over redistricting records

- Article •

- 6/8/2021

Democrats focus on state elections in push to control Congressional mapmaking

- Article •

- 7/7/2020

Michigan’s push to end gerrymandering offers ‘hope’ for divided nation, advocates say

- Article •

- 6/3/2021

The Impact of Partisan Gerrymandering on Political Parties

- Academic •

- 10/24/2019

Is Gerrymandering to Blame for Our Polarized Politics?

- Academic •

- 2/19/2018

It’s Probably Not Possible To End Gerrymandering

- Podcast •

- 0/11/2018

Texas Redistricting Fight Split Over Party Lines After Census Results

- Video •

- 3/30/2021

Simple Civics | What is Gerrymandering?

- Video •

- 8/15/2020

GerryMander Redistricting Game

- Interactive •

- 0/1/2022

Redistricting Simulator

- Interactive •

- 0/1/2022