Early 20th Century Immigration Restrictions

In the early 20th century, a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States led Congress to impose several restrictive immigration laws.

From the mid-19th century through the early 20th century, millions of people immigrated to the United States in a period historians now commonly refer to as the Age of Mass Migration. This era sparked a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States and inspired some legislators to advocate for stricter immigration limits. Many lawmakers claimed that high rates of immigration increased crime rates, suggesting the massive influx of migrants threatened Americans’ public safety.

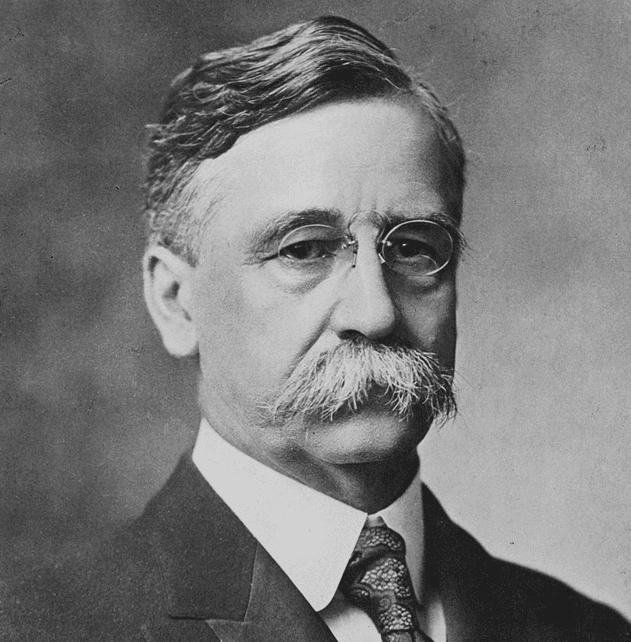

In response, Congress formed the Dillingham Commission in 1907 — named after its Chairman, one of the most emphatic advocates for immigration restrictions — to evaluate existing immigration laws.

Wikipedia

The Commission’s 1911 report was incredibly influential on U.S. immigration policy for decades after, most notably its recommendations that deemed certain European immigrants, particularly eastern and southern ones, less desirable and more prone to criminal behavior than others. The Commission’s policy proposals further advanced the anti-immigrant sentiment in Congress and fueled the slew of immigration restrictions it passed over the next couple of decades.

One of the earliest immigration laws following this report was the Immigration Act of 1917, sometimes known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. The legislation expanded on several nativist laws from the late 1800s that significantly limited Asian immigration. This restrictive Act established a “barred zone” across much of Asia, stretching from the Middle East to Southeast Asia, and prohibited immigration from the area. It also imposed literacy tests for migrants to severely reduce European immigration.

In 1921, Congress further restricted immigration to the United States with the Emergency Quota Act. This Act imposed the first numerical cap on how many immigrants could enter the United States. Many proponents pitched it as a further limit on “undesirable” migrants.

Congress expanded on that law in 1924 with the National Origins Act, making its quotas stricter and permanent. Sometimes called the Johnson-Reed Act, the law capped immigration to two percent of each nationality residing in the United States according to the 1890 census and completely barred Asian immigrants.

America’s ethnicity-based-quotas also led to a complete overhaul of the immigration process. To ensure they could enforce these limits, the government established the visa system we still use today. They also turned Ellis Island, previously one of the nation’s busiest immigration inspection and processing facilities, into a detention center. These policies continued for decades until Congress enacted major reforms to adopt a more ethnically neutral way of controlling immigration.